Private Ownership Limitations And Restrictions

PRIVATE OWNERSHIP LIMITATIONS AND RESTRICTIONS

Encumbrances

Deed restrictions

Easements

Encroachments

Licenses

Leases

Liens

Encumbrances An encumbrance is an interest in and right to real property that limits the legal owner’s freehold interest. In effect, an encumbrance is another’s right to use or take possession of a legal owner’s property, or to prevent the legal owner from enjoying the full bundle of rights in the estate.

An encumbrance does not include the right of possession and is therefore a lesser interest than the owner’s freehold interest. For that reason, encumbrances are not considered estates. However, an encumbrance can lead to the owner’s loss of ownership of the property.

Easements and liens are the most common types of encumbrance. An easement, such as a utility easement, enables others to use the property, regardless of the owner’s desires. A lien, such as a tax lien, can be placed on the property’s title, thereby restricting the owner’s ability to transfer clear title to another party.

The two general types of encumbrance are those that affect the property’s use and those that affect legal ownership, value and transfer.

Deed restrictions A deed restriction is a limitation imposed on a buyer’s use of a property by stipulation in the deed of conveyance or recorded subdivision plat. 212 Principles of Real Estate Practice in Florida

A deed restriction may apply to a single property or to an entire subdivision. A developer may place restrictions on all properties within a recorded subdivision plat. Subsequent re-sales of properties within the subdivision are thereby subject to the plat’s covenants and conditions.

A private party who wants to control the quality and standards of a property can establish a deed restriction. Deed restrictions take precedence over zoning ordinances if they are more restrictive.

Deed restrictions typically apply to:

the land use

the size and type of structures that may be placed on the property

minimum costs of structures

engineering, architectural, and aesthetic standards, such as setbacks or specific standards of construction

Deed restrictions in a subdivision, for example, might include a minimum size for the residential structure, setback requirements for the home, and prohibitions against secondary structures such as sheds or cottages.

Deed restrictions are either covenants or conditions. A condition can only be created within a transfer of ownership. If a condition is later violated, a suit can force the owner to forfeit ownership to the previous owner. A covenant can be created by mutual agreement. If a covenant is breached, an injunction can force compliance or payment of compensatory

Easements An easement is an interest in real property that gives the holder the right to use portions of the legal owner’s real property in a defined way. Easement rights may apply to a property’s surface, subsurface, or airspace, but the affected area must be defined.

The receiver of the easement right is the benefited party; the giver of the easement right is the burdened party.

Essential characteristics of easements include the following:

An easement must involve the owner of the land over which the easement runs, and another, non-owning party. One cannot own an easement over one’s own property.

an easement pertains to a specified physical area within the property boundaries

an easement may be affirmative, allowing a use, such as a right-of-way, or negative, prohibiting a use, such as an airspace easement that prohibits one property owner from obstructing another’s ocean view

The two basic types of easement are appurtenant and gross.

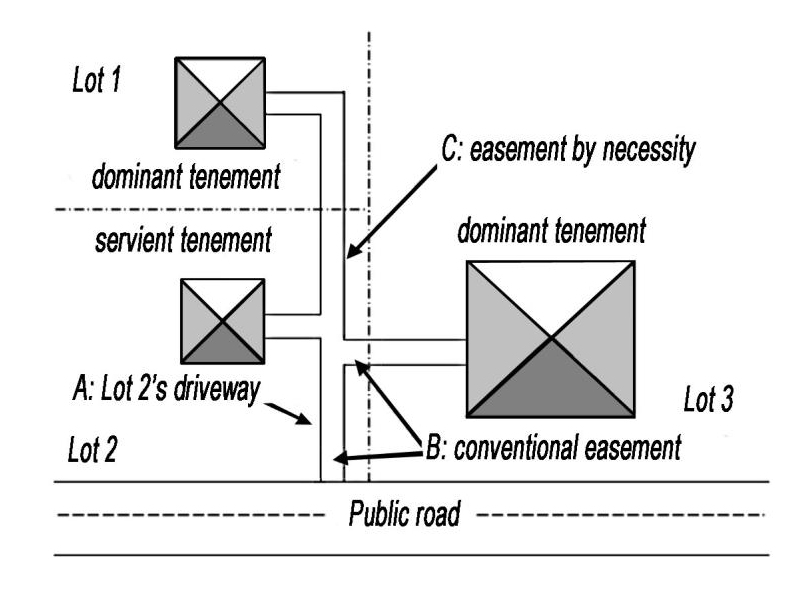

Easement appurtenant. An easement appurtenant gives a property owner a right of usage to portions of an adjoining property owned by another party. The property enjoying the usage right is called the dominant tenement, or dominant estate. The property containing the physical easement itself is the servient tenement, since it must serve the easement use.

The term appurtenant means “attaching to.” An easement appurtenant attaches to the estate and transfers with it unless specifically stated otherwise in the transaction documents. More specifically, the easement attaches as a beneficial interest to the dominant estate, and as an encumbrance to the servient estate. The easement appurtenant then becomes part of the dominant estate’s bundle of rights and the servient estate’s obligation, or encumbrance.

Transfer. Easement appurtenant rights and obligations automatically transfer with the property upon transfer of either the dominant or servient estate, whether mentioned in the deed or not. For example, John grants Mary the right to share his driveway at any time over a five-year period, and the grant is duly recorded. If Mary sells her property in two years, the easement right transfers to the buyer as part of the estate.

Non-exclusive use. The servient tenement, as well as the dominant tenement, may use the easement area, provided the use does not unreasonably obstruct the dominant use.

use #2’s driveway. Parcel #3 is the dominant tenement, and #2 is the servient tenement.

Easement by necessity. An easement by necessity is an easement appurtenant granted by a court of law to a property owner because of a circumstance of necessity, most commonly the need for access to a property. Since property cannot be legally landlocked, or without legal access to a public thoroughfare, a court will grant an owner of a landlocked property an easement by necessity over an adjoining property that has access to a thoroughfare. The landlocked party becomes the dominant tenement, and the property containing the easement is the servient tenement.

In the exhibit, parcel #1, which is landlocked, owns an easement by necessity, marked C, across parcel #2.

Party wall easement. A party wall is a common wall shared by two separate structures along a property boundary.

Party wall agreements generally provide for severalty ownership of half of the wall by each owner, or at least some fraction of the width of the wall. In addition, the agreement grants a negative easement appurtenant to each owner in the other’s wall. This is to prevent unlimited use of the wall, in particular a destructive use that would jeopardize the adjacent property owner’s building. The agreement also establishes responsibilities and obligations for maintenance and repair of the wall.

For example, Helen and Troy are adjacent neighbors in an urban housing complex having party walls on property lines. They both agree that they separately own the portion of the party wall on their property. They also grant each other an easement appurtenant in their owned portion of the wall. The easement restricts any use of the wall that would impair its condition. They also agree to split any repairs or maintenance evenly.

Other structures that are subject to party agreements are common fences, driveways, and walkways.

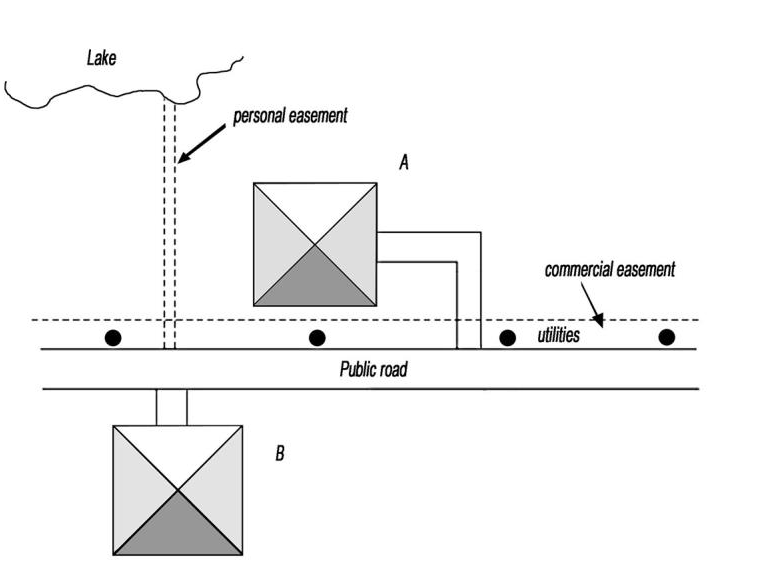

Easement in gross. An easement in gross is a personal right that one party grants to another to use the grantor’s real property. The right does not attach to the grantor’s estate. It involves only one property, and, consequently, does not benefit any property owned by the easement owner. There are no dominant or servient estates in an easement in gross. An easement in gross may be personal or commercial. Section 9: Title, Deeds, and Ownership Restrictions 215

Easements in Gross

personal — A personal easement in gross is granted for the grantee’s lifetime. The right is irrevocable during this period, but terminates on the grantee’s death. It may not be sold, assigned, transferred, or willed. A personal gross easement differs from a license in that the grantor of a license may revoke the usage right. The exhibit shows that a beachfront property owner (A) has granted a neighbor (B) across the street the right to cross A’s property to reach the beach.

commercial — a commercial easement in gross is granted to a business entity rather than a private party. The duration of the commercial easement is not tied to anyone’s lifetime. The right may by assigned, transferred, or willed.

Examples of commercial gross easements include:

a marina’s right-of-way to a boat ramp

a utility company’s right-of-way across a lot owners’ property to install and maintain telephone lines (as illustrated in the exhibit)

Easement creation. An easement may be created by voluntary action, by necessary or prescriptive operation of law, and by government power of eminent domain.

voluntary— a property owner may create a voluntary easement by express grant in a sale contract, or as a reserved right expressed in a deed

necessity — s court decree creates an easement by necessity to provide access to a landlocked property

Easement by prescription. If someone uses another’s property as an easement without permission for a statutory period of time and under certain conditions, a court order may give the user the easement right by prescription, regardless of the owner’s desires.

For a prescriptive easement order to be granted, the following circumstances must be true:

adverse and hostile use — the use has been occurring without permission or license

open and notorious use — the owner knows or is presumed to have known of the use

continuous use — the use has been generally uninterrupted over the statutory prescriptive period

For example, a subdivision owns an access road, which is also used by other neighborhoods to access a grocery store. One day, the subdivision blocks off the road, claiming it has never granted the neighbors permission to use the road. If the neighbors have been using the road for the prescribed period, they may sue for an easement by prescription, since the subdivision owners can be assumed to have known of the usage.

Eminent domain. Government entities can create easements through the exercise of eminent domain, wherein they condemn a portion of a property and cause it to be sold “for the greater good.” A typical example is a town’s condemnation of private land to create a new municipal sewer system.

Easement termination. Easements terminate by:

express release of the right by the easement holder

merger, as when a dominant tenement acquires the servient property, or vice versa

purposeful abandonment by the dominant tenement

condemnation through eminent domain

change or cessation of the purpose for the easement

destruction of an easement structure, such as a party fence

non-use of an easement by prescription

Encroachments An encroachment is the unauthorized, physical intrusion of one owner’s real property into that of another. Section 9: Title, Deeds, and Ownership Restrictions 217

Examples of encroachments are:

a tree limb extending into the neighbor’s property, violating his or her airspace

a driveway extending beyond the lot line onto the neighbor’s land

a fence built beyond the property line

Encroachments cause infringements on the rights of the trespassed owner, and may diminish the property’s value, particularly when the property is to be sold.

Encroachments often do not appear on a property’s title records. A survey may be required to detect or demonstrate the existence of an encroachment.

An owner may sue for removal of an encroachment or for compensation for

damages. If an encroached owner takes no remedial action over a prescribed number of years, the encroachment may become an easement by prescription.

Licenses A license, much like a personal easement in gross, is a personal right that a property owner grants to another to use the property for a specific purpose. Licenses are not transferrable and do not attach to the land. They cease on the death of either party, or on the sale of the property.

Unlike a personal easement in gross, a license is revocable at any time. Licenses are often granted informally, as a verbal statement of permission.

A farmer granting a neighbor permission to cross his land to reach and fish in his pond is an example of a license.

Leases Gross lease. A gross lease, or full service lease, requires the landlord to pay the property’s operating expenses, including utilities, repairs, and maintenance, while the tenant pays only rent. Rent levels under a gross lease are higher than under a net lease, since the landlord recoups expense outlays in the form of added rent.

Gross leases are common for office and industrial properties. Residential leases are usually gross leases with the exception that the tenants often pay utilities expenses.

Net lease. A net lease requires a tenant to pay for utilities, internal repairs, and a proportionate share of taxes, insurance, and operating expenses in addition to rent. In effect, the landlord “passes through” actual property expenses to the tenant rather than charging a higher rent level. Net leases vary as to exactly what expenses the tenant is responsible for. The extreme form of net lease requires tenants to cover all expenses, including major repairs and property taxes.

Net leases are common for office and industrial properties. They are sometimes also used for single family dwellings.

In practice, the terms net and gross lease can be misleading: some gross leases still require tenants to pay some expenses such as utilities and repairs. Similarly, some net leases require the landlord to pay certain expenses. Prudent tenants and 218 Principles of Real Estate Practice in Florida

landlords look at all expense obligations in relation to the level of rent to be charged.

Percentage lease. A percentage lease allows the landlord to share in the income generated from the use of the property. A tenant pays percentage rent, or an amount of rent equal to a percentage of the tenant’s periodic gross sales. The percentage rent may be:

a fixed percent of gross revenue without a minimum rent

a fixed minimum rent plus an additional percent of gross sales

a percentage rent or minimum rent, whichever is greater

Percentage leases are used only for retail properties.

Variable/index. A variable lease is an agreement for the tenant to pay specified rent increases at set dates in the future. The increases may be based on a variable interest rate, a Consumer Price Index (CPI), a percentage of sales, or some other variable factor. The lease must state how the rent increases are to be calculated. An index lease agreement typically calculates the rent increases based on the CPI so that an increase in the CPI will result in a corresponding increase in the rent payment.

Residential lease. A residential lease may be a net lease or a gross lease. Usually, it is a form of gross lease in which the landlord pays all property expenses except the tenant’s utilities and water. Since residential leases tend to be short in term, tenants cannot be expected to pay for major repairs and improvements. The landlord, rather, absorbs these expenses and recoups the outlays through higher rent.

Residential leases differ from commercial and other types of lease in that:

lease terms are shorter, typically one or two years

lease clauses are fairly standard from one property to the next, in order to reflect compliance with local landlord-tenant relations laws

lease clauses are generally not negotiable, particularly in larger apartment complexes where owners want uniform leases for all residents

Commercial lease. A commercial lease may be a net, gross, or percentage lease, if the tenant is a retail business. As a rule, a commercial lease is a significant and complex business proposition. It may involve hundreds of thousands of dollars for improving the property to the tenant’s specifications. Since the lease terms are often long, total rent liabilities for the tenant can easily be millions of dollars.

Some important features of commercial leases are:

long term, ranging up to 25 years

require tenant improvements to meet particular usage needs

Section 9: Title, Deeds, and Ownership Restrictions 219

virtually all lease clauses are negotiable due to the financial magnitude of the transaction

default can have serious financial consequences; therefore, lease clauses must express all points of agreement and be very precise

Ground lease . A ground lease, or land lease, concerns the land portion of a real property. The owner grants the tenant a leasehold interest in the land only, in exchange for rent.

Ground leases are primarily used in three circumstances:

an owner wishes to lease raw land to an agricultural or mining interest

unimproved property is to be developed and either the owner wants to retain ownership of the land, or the developer or future users of the property do not want to own the land

the owner of an improved property wishes to sell an interest in the improvements while retaining ownership of the underlying land

In the latter two instances, a ground lease offers owners, developers, and users various financing, appreciation, and tax advantages. For example, a ground lease lessor can take advantage of the increase in value of the land due to the new improvements developed on it, without incurring the risks of developing and owning the improvements. Land leases executed for the purpose of development or to segregate ownership of land from ownership of improvements are inherently long term leases, often ranging from thirty to fifty years.

Proprietary lease. A proprietary lease conveys a leasehold interest to an owner of a cooperative. The proprietary lease does not stipulate rent, as the rent is equal to the owner’s share of the periodic expenses of the entire cooperative. The term of the lease is likewise unspecified, as it coincides with the ownership period of the cooperative tenant: when an interest is sold, the proprietary lease for the seller’s unit is assigned to the new buyer.

Leasing of rights. The practice of leasing property rights other than the rights to exclusive occupancy and possession occurs most commonly in the leasing of water rights, air rights, and mineral rights.

For example, an owner of land that has deposits of coal might lease the mineral rights to a mining company, giving the mining company the limited right to extract the coal. The rights lease may be very specific, stating how much of a mineral or other resource may be extracted, how the rights may be exercised, for what period of time, and on what portions of the property. The lessee’s rights do not include common leasehold interests such as occupancy, exclusion, quiet enjoyment, or possession of the leased premises.

Another example of a rights lease is where a railroad wants to erect a bridge over a thoroughfare owned by a municipality. The railroad must obtain an air rights 220 Principles of Real Estate Practice in Florida

agreement of some kind, whether it be an easement, a purchase, or a lease, before it can construct the bridge.

Sale subject to lease. Sometimes when a property is being sold, the contract includes a “subject to” clause. If the property has been a rental property prior to the sale, the seller may want to assure the tenant is protected and allowed to continue leasing the property under the new owner. In such cases, the seller may include a “subject to lease” clause or statement on the contract. By signing the contract, the buyer has agreed to purchase the property with a lease remaining in effect as it stands prior to the sale.

Subletting and assignment. Subletting (subleasing) is the transfer by a tenant, the sublessor, of a portion of the leasehold interest to another party, the sublessee, through the execution of a sublease. The sublease spells out all of the rights and obligations of the sublessor and sublessee, including the payment of rent to the sublessor. The sublessor remains primarily liable for the original lease with the landlord. The subtenant is liable only to the sublessor.

For example, a sublessor subleases a portion of the occupied premises for a portion of the remaining term. The sublessee pays sublease rent to the sublessor, who in turn pays lease rent to the landlord.

An assignment of the lease is a transfer of the entire leasehold interest by a tenant, the assignor, to a third party, the assignee. There is no second lease, and the assignor retains no residual rights of occupancy or other leasehold rights unless expressly stated in the assignment agreement. The assignee becomes primarily liable for the lease and rent, and the assignor, the original tenant, remains secondarily liable. The assignee pays rent directly to the landlord.

All leases clarify the rights and restrictions of the tenant regarding subleasing and assigning the leasehold interest. Generally, the landlord cannot prohibit either act, but the tenant must obtain the landlord’s written approval. The reason for this requirement is that the landlord has a financial stake in the creditworthiness of any prospective tenant.

Liens Lien characteristics. A lien is a creditor’s claim against personal or real property as security for a debt of the property owner. If the owner defaults, the lien gives the creditor the right to force the sale of the property to satisfy the debt.

For example, a homeowner borrows $5,000 to pay for a new roof. The lender funds the loan in exchange for the borrower’s promissory note to repay the loan. At the same time, the lender places a lien on the property for $5,000 as security for the debt. If the borrower defaults, the lien allows the lender to force the sale of the house to satisfy the debt.

The example illustrates that a lien is an encumbrance that restricts free and clear ownership by securing the liened property as collateral for a debt. If the owner sells the property, the lienholder is entitled to that portion of the sales proceeds Section 9: Title, Deeds, and Ownership Restrictions 221

needed to pay off the debt. In addition, a defaulting owner may lose ownership altogether if the creditor forecloses.

In addition to restricting the owner’s bundle of rights, a recorded lien effectively reduces the owner’s equity in the property to the extent of the lien amount.

The creditor who places a lien on a property is called the lienor, and the debtor who owns the property is the lienee.

Liens have the following legal features:

a lien does not convey ownership, with one exception

A lienor generally has an equitable interest in the property, but not legal ownership. The exception is a mortgage lien on a property in a title-theory state (Florida is a lien-theory state). In title-theory states, the mortgage transaction conveys legal title to the lender, who holds it until the mortgage obligations are satisfied. During the mortgage loan period, the borrower has equitable title to the property.

a lien attaches to the property

If the property is transferred, the new owner acquires the lien securing the payment of the debt. In addition, the creditor may take foreclosure action against the new owner for satisfaction of the debt.

a property may be subject to multiple liens

There may be numerous liens against a particular property. The more liens there are recorded against property, the less secure the collateral is for a creditor, since the total value of all liens may approach or exceed the total value of the property.

A lien terminates on payment of the debt and recording of documents

Payment of the debt and recording of the appropriate satisfaction documents ordinarily terminate a lien. If a default occurs, a suit for judgment or foreclosure enforces the lien. These actions force the sale of the property. 222 Principles of Real Estate Practice in Florida

Liens may be voluntary or involuntary, general or specific, and superior or inferior.

Voluntary or involuntary lien. A property owner may create a voluntary lien to borrow money or some other asset secured by a mortgage. An involuntary lien is one that a legal process places against a property regardless of the owner’s desires.

If statutory law imposes an involuntary lien, the lien is a statutory lien. A real estate tax lien is a common example. If court action imposes an involuntary lien, the lien is an equitable lien. An example is a judgment lien placed on a property as security for a money judgment.

General or specific lien. A general lien is one placed against any and all real and personal property owned by a particular debtor. An example is an inheritance tax lien placed against all property owned by the heir. A specific lien attaches to a single item of real or personal property, and does not affect other property owned by the debtor. A conventional mortgage lien is an example, where the property is the only asset attached by the lien.

Lien priority. The category of superior, or senior, liens ranks above the category of inferior, or junior, liens, meaning that superior liens receive first payment from the proceeds of a foreclosure. The superior category includes liens for real estate tax, special assessments, and inheritance tax. Other liens, including income tax liens, are inferior.

Within the superior and inferior categories, a ranking of lien priority determines the order of the liens’ claims on the security underlying the debt. The highest ranking lien is first to receive proceeds from the foreclosed and liquidated security. The lien with lowest priority is last in line. The owner receives any sale proceeds that remain after all lienors receive their due.

Lien priority is of paramount concern to the creditor, since it establishes the level of risk in recovering loaned assets in the event of default.

Two factors primarily determine lien priority:

the lien’s categorization as superior or junior

the date of recordation of the lien

Superior liens. All superior liens take precedence over all junior liens regardless of recording date, since they are considered to be matters of public record not requiring further constructive notice. Thus, a real estate tax lien (senior) recorded on June 15 has priority over an income tax lien (junior) recorded on June 1. Superior liens include real estate tax liens, special assessment liens, and federal and state inheritance liens.

real estate tax lien The local legal taxing authority annually places a real estate tax lien, also called an ad valorem tax lien, against properties as security for payment of the annual property tax. The amount of a particular lien is based on the taxed property’s assessed value and the local tax rate.

special assessment lien Local government entities place assessment liens against certain properties to ensure payment for local improvement projects such as new roads, schools, sewers, or libraries. An assessment lien applies only to properties that are expected to benefit from the municipal improvement.

224 Principles of Real Estate Practice in Florida

federal and state inheritance tax liens Inheritance tax liens arise from taxes owed by a decedent’s estate. The lien amount is determined through probate and attaches to both real and personal property.

Junior liens. A junior lien is automatically inferior, or subordinate, to a superior lien. Among junior liens, date of recording determines priority. The rule is: the earlier the recording date of the lien, the higher its priority. For example, if a judgment lien is recorded against a property on Friday, and a mortgage lien is recorded on the following Tuesday, the judgment lien has priority and must be satisfied in a foreclosure ahead of the mortgage lien.

The mechanic’s lien (see further below) is an exception to the recording rule. Its priority dates from the point in time when the work commenced or materials were first delivered to the property, rather than from when it was recorded.

Junior liens include other tax liens, judgment liens, mortgage and trust deed liens, vendor’s liens, municipal utility liens, and mechanic’s liens.

other tax liens All tax liens other than those for ad valorem, assessment, and estate tax are junior liens. They include:

federal income tax lien — placed on a taxpayer’s real and personal property for failure to pay income taxes

state corporate income tax lien — filed against corporate property for failure to pay taxes

state intangible tax lien — filed for non-payment of taxes on intangible property

state corporation franchise tax lien — filed to ensure collection of fees to do business within a state

judgment lien A judgment lien attaches to real and personal property as a result of a money judgment issued by a court in favor of a creditor. The creditor may obtain a writ of execution to force the sale of attached property and collect the debt. After paying the debt from the sale proceeds, the debtor may obtain a satisfaction of judgment to clear the title records on other real property that remains unsold.

During the course of a lawsuit, the plaintiff creditor may secure a writ of attachment to prevent the debtor from selling or concealing property. In such a case, there must be a clear Section 9: Title, Deeds, and Ownership Restrictions 225

likelihood that the debt is valid and that the defendant has made attempts to sell or hide property.

Certain properties are exempt from judgment liens, such as homestead property and joint tenancy estates.

mortgage and trust deed lien In lien-theory states (such as Florida), mortgages and trust deeds secure loans made on real property. In these states, the lender records a lien as soon as possible after disbursing the funds in order to establish lien priority.

vendor’s lien A vendor’s lien, also called a seller’s lien, secures a purchase money mortgage, a seller’s loan to a buyer to finance the sale of a property.

municipal utility lien A municipality may place a utility lien against a resident’s real property for failure to pay utility bills.

mechanic’s lien A mechanic’s lien secures the costs of labor, materials, and supplies incurred in the repair or construction of real property improvements. If a property owner fails to pay for work performed or materials supplied, a worker or supplier can file a lien to force the sale of the property and collect the debt. Any individual who performs approved work may place a mechanic’s lien on the property to the extent of the direct costs incurred. Note that unpaid subcontractors may record mechanic’s liens whether the general contractor has been paid or not. Thus it is possible for an owner to have to double-pay a bill in order to eliminate the mechanic’s lien if the general contractor neglects to pay the subcontractors. The mechanic’s lienor must enforce the lien within a certain time period, or the lien expires. In contrast to other junior liens, the priority of a mechanic’s lien dates from the time when the work was begun or completed. For example, a carpenter finishes a job on May 15. The owner refuses to pay the carpenter in spite of the carpenter’s two-month collection effort. Finally, on August 1, the carpenter places a mechanic’s lien on the property. The effective date of the lien for purposes of lien priority is May 15, not August 1.

226 Principles of Real Estate Practice in Florida

The following example illustrates how lien priority works in paying off secured debts. A homeowner is foreclosed on a second mortgage taken out in 2018 for $25,000. The first mortgage, taken in 2016, has a balance of $150,000. Unpaid real estate taxes for the current year are $1,000. There is a $3,000 mechanic’s lien on the property for work performed in 2017. The home sells for $183,000.

The proceeds are distributed in the following order:

1. $1,000 real estate taxes

2. $150,000 first mortgage

3. $3,000 mechanic’s lien

4. $25,000 second mortgage

5. $4,000 balance to the homeowner

Note the risky position of the second mortgage holder: the property had to sell for at least $179,000 for the lender to recover the $25,000.

Subordination. A lienor can change the priority of a junior lien by voluntarily agreeing to subordinate, or lower, the lien’s position in the hierarchy. This change is often necessary when working with a mortgage lender who will not originate a mortgage loan unless it is senior to all other junior liens on the property. The lender may require the borrower to obtain agreements from other lien holders to subordinate their liens to the new mortgage.

For example, interest rates fall from 8% to 6.5% on first mortgages for principal residences. A homeowner wants to refinance her mortgage, but she also has a separate home-equity loan on the house. Since the first-mortgage lender will not accept a lien priority inferior to a home equity loan, the homeowner must persuade the home equity lender to subordinate the home equity lien to the new first-mortgage lien.